The first bird I ever knowingly saw was an American robin. It was the bird I was looking at when, to my mother’s astonishment, the first words to ever come out of my mouth besides “Mama” were uttered: “Look! See the bird!”

Boyhood Birds: Robins, Osprey, Loons, and Eagles

The first bird I ever knowingly saw was an American robin. It was the bird I was looking at when, to my mother’s astonishment, the first words to ever come out of my mouth besides “Mama” were uttered: “Look! See the bird!” Not sure why she was so surprised as I was nearer to two years old than one when this happened. Slow learner. My memory of both bird and event are purely from countless retelling of this family story. Whether because of the tale or kismet or both the robin is my favorite bird to this day.

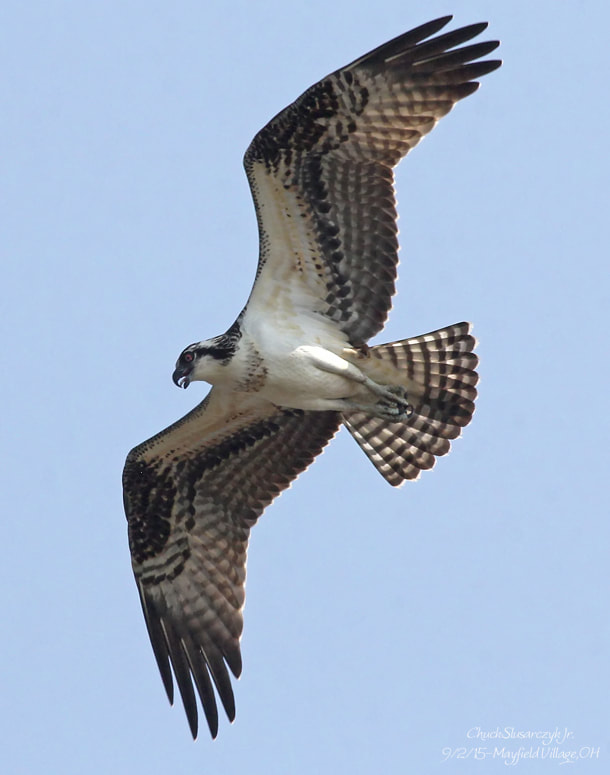

Ospreys

I do clearly remember very specifically the first time I saw an osprey. It was when I was six years old. My father and I went to a local baseball game in Bay Head in Ocean County, New Jersey. Perched, seemingly precariously, on a light pole down the right field line was an enormous nest with an adult bird perched on its edge. Dad excitedly said, “Look Billy, an osprey! That nest has been here for a long time.” He explained to me that the bird was probably feeding young with fish caught in nearby Barnegat Bay.

Loons

My first loon was on Lower Rideau Lake in Portland, Ontario, when I was nine years old. Every summer for five years in the 1950s our family took vacation on this wonderful lake. The exotic “North” seemed to be a true world apart from our Bergen County, New Jersey, home. Farmers still cut hay and worked their farms with horse-drawn equipment. Local maple syrup was sold roadside in old liquor bottles, Great ice cream was two cents a scoop at the marina shop where our rented fishing boat was docked. It was in this boat, a lovely 15-foot Canadian Angler Cedarstrip Runabout, that my family set out to see the loon nest reported by a local as located “two bays down.” We had heard the loons calling. When we came to the bay we saw two loons near a small raised hummock surrounded by water a very short distance from the shoreline. In the nest were two absolutely beautiful eggs. We looked from a distance and left the prospective parents in peace.

Loons are one of the oldest groups of birds on Earth with a history of more than 50 million years. Human activities have decreased the abundance and breeding range of common loons in North America in the last two centuries. Following severe population declines, they are now considered to be stable. This truly wild bird of the north country is very territorial and needs space and peace to reproduce. In Vermont, Eric Hanson has worked tirelessly for loon conservation. Since 1998, Eric has been the biologist for the Vermont Loon Conservation Project, a joint effort between Vermont Center for Ecostudies and the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department. With the annual help of more than 300 volunteers to monitor population, protect nesting sites, and educate the public on how to help loons, the common loon was taken off Vermont’s endangered species list in 2005. In the mid-1980s there were only seven breeding pairs in the state, today there are 70. Work by conservation groups similar to that in Vermont has also been successful in other loon states. Work led by Eric and others is critical to protecting this wonderful bird in the U.S. and Canada, where I saw my first loon, is the world’s loon nursery. Over 94 percent of the breeding common loon population resides in Canada with the majority of these loons in Ontario and Quebec. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, total estimated breeding population is 252,000 to 264,000 territorial pairs. Besides Canada and the U.S., the common loon nests in Iceland and Greenland. When incorporating non-breeding loons, world population is estimated at 607,000 to 635,000, and by fall migration, the young-of-the-year temporarily increase the total population to between 710,000 and 743,000. Common loons winter all along both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of North America as well as in the Gulf of Mexico. The Canadian Lakes Loon survey, run by Bird Studies Canada and supported by thousands of volunteer loon watchers, monitors Canadian loons and provides vital information for loon conservation. Thanks to protection and conservation measures and generous volunteer time, today it is still possible for a boy or girl to be as lucky as I was all those years ago on Lower Rideau Lake to see one of these amazing birds. Long may it be so.  Photo: Eagle (Accipitridae) by Chuck Slusarczyk Jr. Photo: Eagle (Accipitridae) by Chuck Slusarczyk Jr.

Eagles It was also in Ontario that I saw my first bald eagle. My father, sister and I took our boat across the Lower Rideau to an island with what seemed to me to have an impossibly tall tree on it. We set out early one summer morning to see the eagles’ nest. By the 1950s there were already very few bald eagles in the Eastern U.S. and none anywhere near Bergen County, New Jersey. My memory of the day was of high anticipation crowned by slight puzzlement and disappointment when the eagles actually appeared. Running along the lake at the top speed that our 7.5 horsepower Evinrude could manage—about 15 miles per hour—was exciting. We went a long way, the furthest from home base I ever recall. As the destination came into view we saw five or six other boats around, many more than the occasional one or two others—if any at all—spotted at our usual destinations. All were there to see eagles. The nest was huge, and there were two eagles circling high above the island. So high in fact we could hardly make out white heads and tails, but they were clearly big birds, the largest I had ever seen. But so far away! Like all the other boats in the area, we stayed far off the island and we floated for only a few minutes before heading back. I don’t recall any exchange of words after my father said to us, “There they are.” On recollection, he was very solemn at this point in our outing, and that was unusual. I wonder if he might have been saddened by the diminishing numbers—already near extirpation—of bald eagles from our home state. A few years later I saw my second bald eagle. It was in a birch tree, up about 15 feet, as we came around a bend in a canoe on the Delaware River near Port Jervis, New York. Magnificent! It just got worse for bald eagles during my growing up years and into my early adulthood. Already, like the loon, extraordinarily reduced from estimated precolonial numbers throughout the U.S., the horrid DDT really decimated eagle populations. In 1963 there were only just over 400 bald eagle nesting sites in the entire lower 48 states. By the 1980s there was only a single pair of nesting eagles in my native state of New Jersey, and that nest failed for six years in a row.

Alice, an eagle raised in Manhattan by human caretakers until she could be released in the wild in 2004, somehow found Al and the pair successfully raised young on Overpeck Creek in Ridgefield Park in 2011, 2012, and 2013. This is very close the the Hackensack River. It seems unbelievable to me and would have seemed impossible to my father that eagles could even be resident much less breeding in Bergen County—even in the wilder and less settled county of my boyhood, or in the Hackensack River basin my father explored as a boy in the early 20th century.

And to cap this all off, New Jersey naturalist Jim Wright and friends spotted 11 bald eagles in one tree in January 2014 in the nearby Meadowlands. That is probably more eagles than existed in the entire state in my youth. The full story of the return of eagles in New Jersey is wonderfully told by the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission: Read the free e-book online on your computer.

Big Birds, Small Birds The nostalgic recollections of my first sighting of those three big birds many years ago is sweetened by the knowledge that ospreys, loons, and eagles can be seen by more boys and girls today than could be seen all that time ago. Sadly, the same is not true of many of the migrant songbirds of my youth. The orioles, thrushes, flycatchers, wood warblers, vireos, and tanagers that excite us when they return to our parks, gardens, and woods every spring—as they have done for millennia—are under threat. As my friend and colleague Bridget Stutchbury documents in her book Silence of the Songbirds, the threats to these neotropical migrants are growing in both worlds they inhabit and along the migration paths they follow by instincts we will never fully understand. One of my favorite songbirds, the wood thrush, is an extreme example of the problem. The global wood thrush population has plummeted in the past 50 years. From Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds we learn: “Wood Thrush are still common throughout the deciduous forests of eastern North America, but populations declined by almost 2 percent per year between 1966 and 2010, resulting in a cumulative decline of 55 percent, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey”.

Drink Shade-Grown Coffee

There are many dedicated professionals working on learning how to protect the songbirds we share with people throughout the Americas, from the boreal forest to the tropical forests of Latin America. In her book, Stutchbury provides us with a guide to how we as individuals can help turn the tide of population decline for these birds of two worlds that we all love. Easy behavioral advice to follow:

It never occurred to me as a boy that so many factors affect the viability of bird populations. I am really grateful that so many men and women through their careers and their volunteer work have helped the big birds of my boyhood survive and even thrive. I hope we will all, in our daily behavior and our advocacy keep up the tradition of bird conservation so boys and girls throughout the Americas will be able to tell their grandchildren tales of the birds that thrilled them when they were young.

Join the Western Cuyahoga Audubon Bird-Friendly Coffee Club!

Order Shade Grown Coffee online at the Western Cuyahoga Audubon Store (selections below) or download the order form to send a check here. Coffee can also be purchased at monthly Chapter Member and Speaker meetings here.

Make A Donation to Western Cuyahoga Audubon. Your gifts guarantee chapter activities, programs and research continues to reach members and connect to birding conservationists around the world. Use our safe and secure PayPal payment button below to make a donation of any amount you choose. All donations are gratefully received.

Comments

|

Story BlogThe Feathered Flyer blog publishes human interest stories about birding and habitat conservation. After watching, ‘My Painted Trillium Quest' by Tom Fishburn, Kim Langley, WCAS Member said, “Wonderful! It was a lift just knowing that such a site exists and is being protected!”

Media LibrariesQuarterly NewsletterSTORIESPodcastsWCAS is a proud member of The Council of Ohio Audubon Chapters (COAC) and promotes chapter development by sharing the best practices, brainstorming solutions to common problems, and building relationships in workshops and retreats. Subscribe

VideosYouth

Advocacy

Clean Energy

Reporting

Awards

Volunteerism

Take ActionResourcesBlogsArchives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

EDUCATENews Blog

Monthly Speakers Field Reports Bird Walk Reports Christmas Bird Count-Lakewood Circle Media Library Newsletter Archive Education Resources STORE |

Western Cuyahoga Audubon Society

4310 Bush Avenue Cleveland, Ohio 44109 [email protected] Western Cuyahoga Audubon Society is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Your donation is tax-deductible. The tax ID number is: 34-1522665. If you prefer to mail your donation, please send your check to: Nancy Howell, Western Cuyahoga Audubon Treasurer, 19340 Fowles Rd, Middleburg Hts, OH 44130. © 2020 Western Cuyahoga Audubon Society. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Legal | Store Shipping Rates | Site Map |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed