Courtney Brennan, M.S., Collections Manager, Ornithology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History (CMNH) takes us on a full behind-the-scenes tour of the ornithological preparation process for research collection.

Introduction and Background

Courtney Brennan: My name is Courtney Brennan and I’m the Collections Manager for the Ornithology Department here at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. I’ve been working here for about three years and I started volunteering here in 2010. I got my Bachelor’s in Environmental Science from the Museum of Natural History, which was quickly followed by a Master’s in Environmental Science at Cleveland State University where I studied cadence and geographic variation in the songs of the Veery under my advisor, Dr. Andy Jones. What Are You Passionate About? I am very passionate about nature and I’m a Cleveland, OH native, I grew up in this area, spent lots of time in all the parks in this area.

How Did You Become Interested in Ornithology?

I got very interested in birding in my undergraduate career where I decided I really wanted to make birds the focal point of my research and I wanted to figure out a way to make a career out of it. With the help of Dr. Jones, my graduate career became a possibility here at the Natural History Museum. Specimen Preparation So what we’re going to focus on today is one aspect of my job here which is specimen preparation. Here at the Museum we have over 35,000 birds in our avian specimen collection. I have a group of volunteers that meet every Thursday evening and we just add onto that massive pile of bird data.

Above: Explore more photos at the Courtney Brennan, M.S., Collections Manager, Ornithology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History photo Album on Flickr here. Photos by Betsey Merkel.

Right now we currently have several freezers filled with dead birds and my crew and I do our best to process these birds and turn these little birds into research specimens that are highly valuable to the research community and to the public as well.

Practical Tips to Prevent Bird Kills [00:02:26] One of the important things that I find with our outreach programs is informing people on what they can do to reduce bird kills at their house and in their neighborhood. Most of our birds end up in our freezers because they either flew into windows or they got killed by domestic cats and feral cats. There are several steps people can take to reduce window kills at their houses. The decals on the windows have been shown to not be very effective but what is quite effective is putting strips of tape on the outsides of windows or hanging string or feathers on the outsides of windows and decorative things such as, stained glass windows and window dividers. Anything to break up the window reflection. That is the issue at hand: the birds see the reflection of the natural environment the window is reflecting and they fly straight into it which causes injury and 50% of the time, cause death of the bird. In the United States alone, up to one billion birds die in this way, about 10% of the bird population is estimated. Another huge reason we get birds in our freezer is from cat kills. So, the old saying of putting a bell on your cat, that doesn’t work. Birds don’t know what a bell and a cat is trying to signal to them. The best practice is to just keep your housecat inside if possible. That would reduce cat kills and up to 50 million birds killed in the United States alone just by cats. They are not a natural predator and they shouldn’t be in the environment and so their presence is just detrimental to birds and other mammals, and small creatures as well. Museum Collection Value [00:04:12] So even though the focus of this is showing how our museum specimens are made, the very important part is what happens to the specimens after they’re completed. So as I said before, we have 35,000 specimens in our bird collection here at the museum and we’re just adding on to that, and biological collections make innumerable contributions to science and society as a whole, ranging from many different areas of research from public health and safety to environmental change and tracking how the environment is changing through our biological collections, and of course the traditional taxonomy and systematics. Collections are biological libraries that are irreplaceable and the most valuable thing, in my estimation, that the museum has to offer.

Above: Explore more photos at the Ornithology Preparator's Class, Cleveland Museum of Natural History photo Album on Flickr here. Photos by Betsey Merkel.

you found the bird. With those pieces of information that bird becomes the voucher specimen in time and space that we use in our research collection.

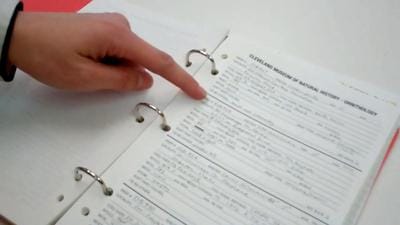

Specimen Preparation Process [00:05:42] Okay, so the very beginning of our specimen preparation begins at the freezers, where birds we get from the public and the rehab centers, they get held in the freezer until we are ready to process them. The birds are roughly organized by taxonomy and priority, so when I find out how many volunteers we’re going to have for the evening, I pull out the necessary specimens and get them thawed out for the volunteers. So once the birds are thawed, our volunteers will turn them into a research specimen. So, here’s my prep area and you can see we use very simple tools. This is a very straight forward process. We are doing it the same way now that they did one hundred years ago. This is where all the action happens. We use ground up corncob dust to keep our hands clean and keep the feathers clean and dry and to absorb moisture during the prep process. Once the birds are prepared and we’re happy with how they look, we pin them to foam boards and we pin in the position we want them to stay in. Bird skin is so thin we just let it air dry, we don’t need to use any hard chemicals to dry them out, so we just pin them in the position we want them to stay and just leave them be in this awesome drying rack built by one of our museum carpenters and they’ll just hang out in the drying rack about a week if it’s a small bird, a few weeks if it’s a larger bird until the skin is fully dried. Once the skin is fully dried all of the information all of our volunteers jotted down while preparing the bird, is transcribed onto these data tags. These data tags stay with the specimen forever and this information gets catalogued and digitized and is associated with this bird for the rest of it’s time at the museum. Once the birds have been dried and their tags attached to them, we have another volunteer that catalogues all the birds in the museum book. Once the birds are in the book, that's when they get their accession number and officially become a research specimen and that’s when they go into the -60 degrees Fahrenheit freezer over on the other side of the room for one week. That’s to get all of the possible pests that might have hitched a ride onto the birds while drying or being prepared here in the prep lab. We’ve got open doors and windows and bugs find their way in here so the freezer makes sure that only the specimens are going into our research collection and no hitch hikers! So once they’ve spent their week in the freezer they go down to the collection where they’re permanently housed in back-of-house where they are digitized with all the information that was put into the catalogue and was written on the tags, goes into the database on the computer, which will eventually be put onto VertNet where our collection can be searchable worldwide by researchers and just people interested in birds that we have here at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Once they are digitized and put into our computer collection they are put into the collection itself where they are permanently housed. Our whole collection is organized taxonomically and then by male, female and calendar dates so each bird has it’s own little spot in the collection.

Above: Explore more photos at the Ornithology Preparator's Class, Cleveland Museum of Natural History photo Album on Flickr here. Photos by Betsey Merkel.

One of the first steps our birds take in becoming a research specimen is they get catalogued in our big, large, old-school catalogue books. We have a lovely volunteer, Sue Divito, that will catalogue all of our research specimens for us and their first step in getting into the collection.

In this book, there are some other interesting things. We recently acquired a collection of birds from the Kingman Museum, a small institution in Michigan, USA and they had almost one thousand birds that were not really being curated and they offered that collection if we wanted it. We said, “Absolutely!” So, we have (in the catalogue) a nice series of Kingman collection birds that are all from the same city in Michigan, which is quite interesting, but even more interesting is that all of these birds are from the late eighteen-eighties which is incredible. So now those birds have become a part of our collection and we honor that they’re from the Kingman Museum on their tags. They are now permanently held in our research collection alongside some of the birds we’re preparing today. Preparator Workshop [00:11:27] On Monday’s I send out an email asking who is available Thursday for our “Skinning Night” - what I lovingly call our group of specimen preparators. Once I get a head count, everyone’s got their tool boxes organized here in our lab. Once I know who’s going to be joining us, I come on out and get their bird prepping stations ready. Each volunteer has the same basic toolkit: some thread, some rounded scissors, some small scissors, large tweezers, small tweezers, a scalpel, and a little flashlight. Very simple. Each volunteer also gets their our tub of corncob dust and that’s to keep the bird feathers clean, keep our hands clean, and absorb moisture throughout the prep process. You’ll see we don’t wear gloves when we prepare birds, that’s mostly because we can’t see what we’re doing we really just have to feel it. So, it’s safe and we go through all the precautions of we don’t prep birds if you have a cut on your hand but it’s generally very safe to do this. This is a delicate job, and you really don’t see what you’re doing you have to feel what you’re doing, so cob dust keeps our hands clean, keeps the bird nice and clean and helps us to not have to wash the feathers because they are not very easy to wash. Spread Wing Preparation [00:12:58] Here is a drying, spread wing of a White-fronted Goose. This bird is especially interesting because it came from California. This is what the bird wing will look like when we’re drying it, so we just spread the wing in a natural way and we put pins behind the primaries to hold out the wing and we just want it to be in a natural position. A lot of researchers are doing spread wings to do more morphometric research but measuring the lengths of all the feathers and seeing how those feather lengths vary from female, or from one region of the bird to another region of the bird, so that’s one of the reasons why we keep one of the wings spread. A lot of people ask, “Why do you cut the wing off?” Traditionally, people would spread a wing and keep it attached to the bird but then that specimen takes up twice as much room in the collection. We opted to just remove the one wing and it gets stored in a separate place from the skin but then in that case we have to write two sets of data tags. One tag goes with the wing, and one tag goes with the skin. We want to make each one of our specimens as valuable to as many different kinds of research as possible so we do what we can to get these birds out there in the world. Wide Reaching Research [00:14:26] Our museum collection can serve many different purposes. We’ve had glass blowing artists and woodworkers come in, they just want to look at the birds and get a close up look of the details of the feathers and spread wings. We also do collaborations with undergraduate and graduate students who are looking at research projects. We had a young lady come in and measure all of the leg bones of White-breasted nuthatches in our collection. We also do collaborative work with bigger institutions, like the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) where we’re going to work on a project to try to figure out why some birds are better at avoiding plane collisions than others. The museum collection has a very wide reach. A lot of people ask us what we have and we try to make our collection as available as possible to people who want to utilize this data that we’ve collected.

Above: Explore more photos at the Ornithology Preparator's Class, Cleveland Museum of Natural History photo Album on Flickr here. Photos by Betsey Merkel.

they don’t have a stick and their neck is starting to rip and their heads are falling off. We want our specimens to last as long as possible so we add the stick just as a stabilizer to keep that little specimen strong.

Recording Specimen Data [00:16:22] So, we want to make each one of our specimens as valuable as possible. We do this by taking as much data as possible from each bird that we prepare. All of that information gets jotted down into our Prep Books. You can see each section in the book and you can get an idea of the information that we’re gathering from each bird: the scientific name, the sex of the bird, we try to find out the age of the bird when it died, the collection date, and if somebody wrote their name down of who salvaged the bird for us, it goes on the tag with that bird. If you bring in a bird and write your name down, you’re the official collector of bird. Then of course the obvious: the measurements of the bird, we weigh the bird, we measure it’s wing chord which is the length from the elbow to the tip of the longest feather, and we measure the wing span, and then a lot of birds you can’t tell if it’s male or female by looking at it so you have to actually open the bird up and find it’s gonads. We find their gonads and measure them and then we describe any fat content. So, what condition the bird was in. The Fall migrant birds will have a lot of fat on them because they’re preparing for the big trip down South. We jot if they’re going through any molting process, if they’re growing in any new feathers, and we open up their stomachs to see what they were eating during their time before they died. All of that information gets jotted down in this book. This information gets transcribed onto the small specimen tag that gets attached to the bird and stays with that bird forever. So this is the first point of all of the data that we collect for our birds. Freezer Preparation [00:18:04] After the birds are dried and catalogued, they have to go into the -60 degree freezer for a week before they can be safely moved into our research collection. All of our birds will get placed gently in these giant tubs and then we cover them with cotton and then we double bag each tub. We put one garbage bag over it and then we do another one and then they hang out in the freezer and this creates an environment that no insect or insect eggs can survive, ensuring that only our specimens are going to the collection and not any hitchiker pests. Final Step to Permanent Collection [00:18:45] Once the specimens have been safely packed away in a tub in the freezer for one week in our -60 degree freezer, these specimens are now ready to be transported to our collection where they will be permanently housed. Download: Preparing Tomorrow's Ornithological Discoveries Today with Courtney Brennan, Preparator Above: Courtney Brennan, M.S., Collections Manager, Ornithology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH USA. Photo by Betsey Merkel. Above: Courtney Brennan, M.S., Collections Manager, Ornithology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH USA. Photo by Betsey Merkel.

Courtney L. Brennan, M.S., is Collections Manager, Department of Ornithology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History in Cleveland, Ohio. Courtney’s research is focused on variation in bird song. Courtney earned a Bachelor's of Science, Cleveland State University in 2011 and a Master's of Science at Cleveland State University in 2014. Miss Brennan’s Master’s thesis title is, “Singing Behavior and Geographic Variation in the Songs of the Veery (Catharus fuscescens) across the Appalachian Mountains”.

Graduate advisors were Dr. Andrew W. Jones, Cleveland Museum of Natural History; Dr. Julie Wolin, Cleveland State University; Dr. Robert Krebs, Cleveland State University; and Dr. Michael Horvath, Cleveland State University. View: “Song Structure and Cadence of the Veery (Catharus fuscescens) across the Appalachian Mountains. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 128 (1): 75-85, 2016. Read the Abstract at Research Gate here.

Make A Donation to Western Cuyahoga Audubon. Your gifts guarantee chapter activities, programs and research continues to reach members and connect birding conservationists around the world. Use our safe and secure PayPal payment button below to make a donation of any amount you choose. All donations are gratefully received.

Comments

|

Story BlogThe Feathered Flyer blog publishes human interest stories about birding and habitat conservation. After watching, ‘My Painted Trillium Quest' by Tom Fishburn, Kim Langley, WCAS Member said, “Wonderful! It was a lift just knowing that such a site exists and is being protected!”

Media LibrariesQuarterly NewsletterSTORIESPodcastsWCAS is a proud member of The Council of Ohio Audubon Chapters (COAC) and promotes chapter development by sharing the best practices, brainstorming solutions to common problems, and building relationships in workshops and retreats. Subscribe

VideosYouth

Advocacy

Clean Energy

Reporting

Awards

Volunteerism

Take ActionResourcesBlogsArchives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

EDUCATENews Blog

Monthly Speakers Field Reports Bird Walk Reports Christmas Bird Count-Lakewood Circle Media Library Newsletter Archive Education Resources STORE |

Western Cuyahoga Audubon Society

4310 Bush Avenue Cleveland, Ohio 44109 [email protected] Western Cuyahoga Audubon Society is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Your donation is tax-deductible. The tax ID number is: 34-1522665. If you prefer to mail your donation, please send your check to: Nancy Howell, Western Cuyahoga Audubon Treasurer, 19340 Fowles Rd, Middleburg Hts, OH 44130. © 2020 Western Cuyahoga Audubon Society. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Legal | Store Shipping Rates | Site Map |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed